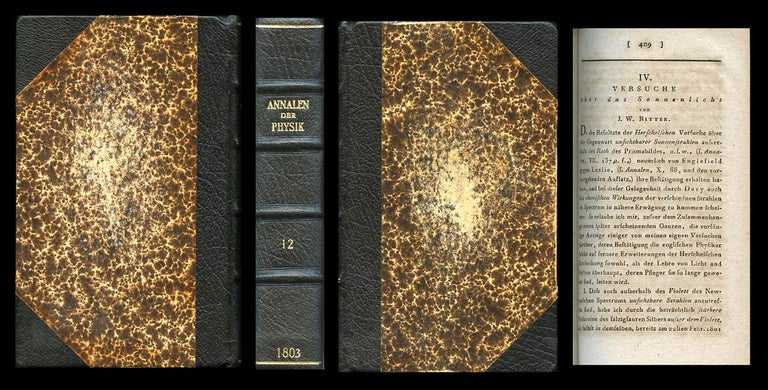

Versuche uber das Sonnenlicht in Annalen der Physik und Chemie 12, 1803, pp. 409-416

Halle: Rengerschen Buchhandlung10, 1803. 1st Edition. FIRST EDITION, FULL VOLUME WITH ORIGINAL FRONT WRAP BOUND IN, OF THE FIRST FULLY DEVELOPED PAPER DESCRIBING RITTER’S DISCOVERY OF ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION. Ritter had ‘announced’ the discovery in a half page letter in the 1802 Annalen. In discovering ultraviolet light, or light without heat, Ritter had discovered an analog to Herschel’s infrared light, or heat without light (Kittler, Optical Media, 123). Ultraviolet radiation is in the part of the electromagnetic spectrum where wavelengths are shorter than that of visible light but longer than X-rays, specifically, it is composed of three types of rays and has a wavelength from 10nm to 400 nm (Wikipedia).

In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared light. To test the temperatures of differently colored light, Herschel channeled sunlight through a prism. The prism split the colors into a rainbow whose colors Herschel had directed to each fall on a different thermometers. The experiment made clear that the highest temperatures occurred where the light did not appear to shine at all — just beyond the red line of the rainbow. Herschel’s experiment demonstrated the first detection of a form of light beyond the visible, ‘infrared’. Herschel’s discovery of ‘infrared’ light strongly indicated that Newton’s chromatic spectrum was only a small part of a much larger phenomenon.

Johann Wilhelm Ritter was a German physicist, chemist, and philosopher. Ritter was particularly engaged by Herschel’s discovery and began to wonder if he could detect invisible light at the other end of the spectrum and beyond the violet or blue lines of the rainbow. Ritter put it more methodically: “if the solar spectrum is brightest in the middle but warmest at its end, then why should cold light not also exist beyond the other end of the visible spectrum” (ibid).

While studying the issue, Ritter speculated that in order to answer his question, he needed “a chemical reagent that has its strongest effect beyond the violet in the same way that our thermometer has its strongest effect beyond the red” (ibid).

While experimenting with silver chloride as a chemical reagent, Ritter noted that it turned black when exposed to light. Ritter had heard that blue light caused a greater reaction in silver chloride than red light did, so he decided to measure the rate at which silver chloride reacted to the different colors of light. “He directed sunlight through a glass prism to create a spectrum and then placed silver chloride in each color of the spectrum and found that it showed little change in the red part of the spectrum, but darkened toward the violet end of the spectrum.

“Ritter then decided to place silver chloride in the area just beyond the violet end of the spectrum, in a region where no sunlight was visible. To his amazement, this region showed the most intense reaction of all. This showed for the first time that an invisible form of light existed beyond the violet end of the visible spectrum. This new type of light, which Ritter called Chemical Rays, later became known as ultraviolet light or ultraviolet radiation (the word ultra means beyond) (Rubin, Newton, Herschel and Ritter, The Discovery of the Spectrum of Light). Item #886

CONDITION & DETAILS: Halle: Rengerschen Buchhandlung. 8vo. (7.5 x 5 inches; 188 x 125mm). Full volume. Complete. Original front wraps and contents pages for each issue are bound in (there is a small tear to the contents page of one of the front wraps). [24], 747, [4]. 5 fold-out plates. Very handsomely rebound in three-quarter black calf over marbled paper boards. Tight, solid, and very clean. Regarding the interior, there is a small tear to the contents page of one of the front wraps attached; other than this, the interior is clean and bright. Very good to near fine condition.

Price: $675.00